When Keir Starmer, Prime Minister of Labour Party told reporters on 3 October 2025 that any asylum seeker who stays put in a hotel will lose both housing and financial assistance, the announcement hit the headlines across the capital. The warning came during a briefing at the Home Office in London, where officials said the move is meant to stop a "growing crisis" that threatens public order and fuels the ongoing small‑boats debate. By threatening to pull support, the government hopes to force a faster move into dispersal accommodation, a policy that has been simmering since the 2021 influx of boats across the Channel.

Historical backdrop: how the hotel boom took hold

London’s reliance on hotels for asylum accommodation has been a slow‑burning disaster. In Q1 2023, the city housed 55 % of its asylum seekers in hotels; by the close of 2024 that share had ballooned to 65 %, according to Home Office data released in May 2025. The national picture looks very different – most regions have been pulling people out of contingency hotels since 2020, when the overall UK hotel‑use peaked at 47 %.

Several factors converged to make the capital an outlier. First, the city’s housing market is already strained, leaving few affordable options for dispersal. Second, activist groups have repeatedly set up legal challenges that stall the transfer of people from hotels to asylum seeker centers. Finally, the 2023‑24 surge in Channel crossings – 12,300 boat arrivals, the highest since 2015 – left the system scrambling for any available beds.

What the new policy actually says

The Home Office released a three‑page directive titled “Conditional Support Framework – Phase II.” In plain English, it means:

- If an asylum seeker refuses a genuine offer of alternative housing, their £176.81 weekly housing allowance and the £109.04 weekly cash‑support payment will be stopped.

- The decision takes effect after a 14‑day notice period, during which the individual can appeal the offer in writing.

- Local authorities will be reimbursed for any costs incurred if the person is later forced to move because of safety concerns.

Officials stress that the policy does not affect people who are already in approved premises; it only targets those who remain in “temporary hotel accommodation” after a formal offer.

Reactions from the front lines

Human‑rights charities were swift to condemn the move. Freedom from Torture issued a statement calling the policy “punitive” and “inconsistent with the UK’s international obligations.” A spokesperson said, “Stripping people of basic support while they wait for a decision on their asylum claim only deepens their vulnerability.”

On the political side, Nigel Farage, leader of Reform UK, praised the crackdown, arguing that “Labour finally understands the pressure on British voters who see illegal crossings and hotel‑squatting as a threat to community safety.” His comments have helped Reform UK maintain a five‑point lead in the latest YouGov poll for the Westminster constituency of Epping, Essex.

Local councils are caught in the middle. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets warned that sudden withdrawals of support could push families onto the streets, exacerbating already‑high levels of rough‑sleeping in the borough.

Impact on the asylum system and the small‑boats debate

Statistically, the pressure is real. In 2024 the Home Office recorded 44,433 asylum refusals, but only 2,636 enforced returns – a figure that barely dents the backlog of 109,500 pending cases as of 31 March 2025. Analysts say the new ultimatum is a way for the government to signal “toughness” ahead of the summer peak, when experts predict another 10,000‑plus boat arrivals.

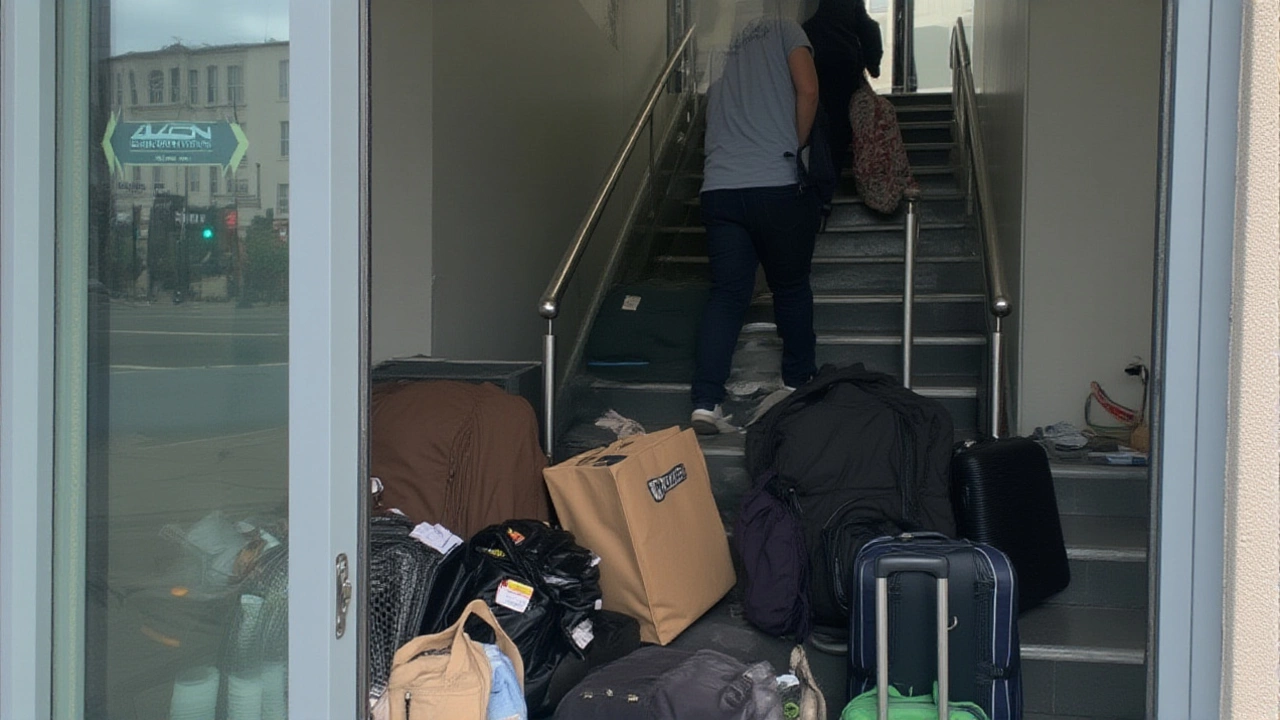

Critics argue the policy could backfire. If people are forced out of hotels without viable housing, they may end up on the streets, increasing the visibility of the crisis and potentially sparking the very unrest the government says it wants to avoid. The summer riots in Epping, Essex – where a far‑right protest turned violent outside an asylum hotel – have already shown how quickly tensions can flare.

What comes next? – The road ahead for London’s asylum seekers

In the short term, the Home Office says it will monitor compliance weekly and adjust offers based on local housing availability. A senior civil servant told reporters that “the goal is to achieve a 30 % reduction in hotel reliance by early 2026.”

Long‑term solutions remain elusive. The government’s broader dispersal plan – moving asylum seekers to regional towns and newly built accommodation hubs – has stalled due to local opposition and funding shortfalls. Some MPs have called for an emergency £500 million housing package, but the Treasury has yet to endorse the request.

Meanwhile, advocacy groups are preparing a legal challenge, arguing that the policy breaches the 1951 Refugee Convention. The case is expected to be heard at the High Court in early 2026.

Frequently Asked Questions

How will the policy affect asylum seekers already living in hotels?

If an individual refuses a bona‑fide offer of alternative accommodation, their weekly housing allowance (£176.81) and cash‑support payment (£109.04) will be stopped after a 14‑day notice. Those who accept an offer keep their support.

What is the government’s rationale behind the crackdown?

Officials say the move is intended to reduce the city’s reliance on costly hotel accommodation, prevent public‑order risks, and pressure the system ahead of the anticipated summer surge in Channel boat arrivals.

Which political parties are supporting or opposing the new rules?

The governing Labour Party backs the policy as a necessary step, while the opposition Conservative Party has criticised its timing. Reform UK, led by Nigel Farage, has praised it as evidence that the government is finally taking the small‑boats issue seriously.

What could happen if the policy leads to more people on the streets?

Housing charities warn that a sudden loss of support could push vulnerable families into rough‑sleeping, raising public‑health concerns and potentially triggering further protests, like the unrest seen in Epping, Essex last summer.

When will the legal challenge against the policy be heard?

Human‑rights groups have filed for a judicial review; the High Court has scheduled a hearing for February 2026, where they will argue that the measure breaches international refugee obligations.